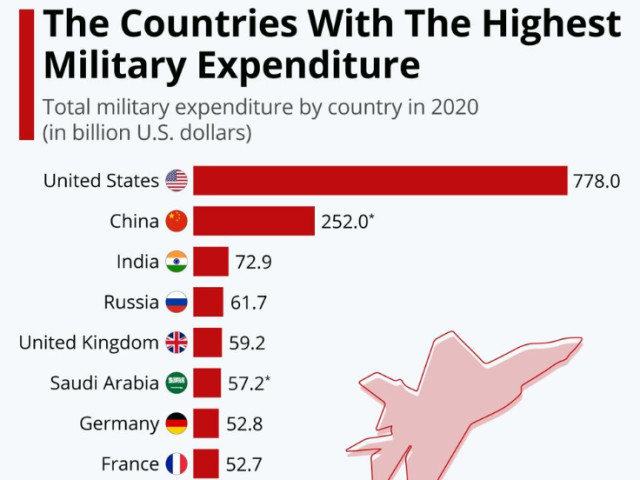

To assess the state of international affairs, a good rule of thumb is to follow the flow of money or weapons. Defence budgets handily track both. A tally released by sipri, a think-tank based in Stockholm, suggests that governments are worried: 102 of the 173 countries included in the study increased their defence budgets last year. Globally, spending in real terms was up by 6.8% from 2022, the largest year-on-year increase since 2009.

Some of the biggest increases came from America’s nato allies in Europe after a long period of low spending. Excluding America, nato members increased spending by $68bn, or 19%, between 2022 and 2023. Adding Finland and Sweden to the alliance has boosted nato’s annual spending by a further $16bn.

But these figures are tricky to compare: the amount spent on wages and fuel, for example, will stretch a lot further in some countries than in others. To get around this, The Economist has adjusted sipri’s estimates for military purchasing-power parity (ppp), with help from Peter Robertson, a researcher at the University of Western Australia.

This makes defence budgets comparable with America’s: pay is adjusted for wage differences and operating costs for general price levels. (Equipment costs are left the same, as much of the kit is imported, and its relative quality is hard to judge.)

The adjustments show that Ukraine’s budget increases (though not its total budget) will stretch further than Russia’s, for example, even though its budget grew at a slightly slower rate in nominal terms (see chart 1). And money spent by America’s allies in nato will matter much more than the dollar figures suggest. Their annual spending in 2023 was just 47.3% of America’s, but adjusted for their lower costs it was 78.5%.

The final ranking shows that America still spends far more on defence than any other country. In 2023 it spent $916bn on its armed forces (see chart 2). Taken together, its 31 allies in nato come in second: they spend $434bn or $719bn adjusted for cost differences.

The alliance’s armed forces are not unified, but it is still useful to compare its spending with others’. Russia and China, for example, respectively spent just 8% and 22% of the nato total in 2023. When that spending is adjusted for military-PPP it is worth 24% and 32% of nato’s outlay.

America’s allies still have further to go. Jens Stoltenberg, nato’s chief, recently said that just 18 members will meet the alliance’s target of spending at least 2% of gdp on defence this year (though that is up from 11 members in 2023).

Some of these figures need to be taken with a pinch of salt. Budget calculations are not consistent across all countries, and not all governments report accurately. (sipri relies on estimates rather than on official numbers for China, for example.)

They also show running costs and investment, not how effective that spending is. But these budgets are nevertheless a good indicator of a country’s military trajectory: they shape what countries will be able to do, and suggest what they plan to do, in the years to come.

The Economist